The Journey Back Began Like This

We’re ending the first year of goop Book Club with one

of the most beautiful books we’ve ever read. The Shadow King opens in 1974, as Hirut is on her way to

meet someone from her past, a journey that drags her back into her memories of Mussolini’s 1935 invasion of

Ethiopia. What follows is a fluid, layered retelling of the conflict, the female soldiers who were left out of the

historical record, and the men on both sides who loved, betrayed, imprisoned, and followed them.

Maaza Mengiste’s epic tale combines an intriguing plot, characters that don’t feel fictional, and

sentences so stunning that you’re forced to pause and take a breath. It was shortlisted for the 2020 Booker

Prize and named a best book of the year by The New York Times when the hardcover was released, in 2019.

It’s out in paperback now. Pick up a copy and hang with us in goop Book Club to talk about it.

Until then, meet the brilliant Hirut.

From The Shadow King

1974

She does not want to remember but she is here and memory is gathering bones. She has come by foot and by bus to

Addis Ababa, across terrain she has chosen to forget for nearly forty years. She is two days early but she will wait

for him, seated on the ground in this corner of the train station, the metal box on her lap, her back pressed

against the wall, rigid as a sentinel. She has put on the dress she does not wear every day. Her hair is neatly

braided and sleek and she has been careful to hide the long scar that puckers at the base of her neck and trails

over her shoulder like a broken necklace.

In the box are his letters, le lettere, ho sepolto le mie lettere, è il mio segreto, Hirut, anche il tuo

segreto. Segreto, secret, meestir. You must keep them for me until I see you again. Now go. Vatene. Hurry before

they catch you.

There are newspaper clippings with dates spanning the course of the war between her country and his. She knows he

has arranged them from the start, 1935, to nearly the end, 1941.

In the box are photographs of her, those he took on Fucelli’s orders and labeled in his own neat handwriting:

una bella ragazza. Una soldata feroce. And those he took of his own free will, mementos scavenged from the

life of the frightened young woman she was in that prison, behind that barbed-wire fence, trapped in terrifying

nights that she could not free herself from.

Inside the box are the many dead that insist on resurrection.

She has traveled for five days to get to this place. She has pushed her way through checkpoints and nervous

soldiers, past frightened villagers whispering of a coming revolution, and violent student protests. She has

watched while a parade of young women, raising fists and rifles, marched past the bus taking her to Bahir Dar.

They stared at her, an aging woman in her long drab dress, as if they did not know those who came before them.

As if this were the first time a woman carried a gun. As if the ground beneath their feet had not been won by

some of the greatest fighters Ethiopia had ever known, women named Aster, Nardos, Abebech, Tsedale, Aziza,

Hanna, Meaza, Aynadis, Debru, Yodit, Ililta, Abeba, Kidist, Belaynesh, Meskerem, Nunu, Tigist, Tsehai, Beza,

Saba, and a woman simply called the cook. Hirut murmured the names of those women as the students marched past,

each utterance hurling her back in time until she was once again on ragged terrain, choking in fumes and

gunpowder, suffocating in the pungent stench of poison.

“One name always drags with it another: nothing travels alone.”

She was brought back to the bus, to the present, only after one old man grabbed her by the arm as he took a

seat next to her: If Mussoloni couldn’t get rid of the emperor, what do these students think they are

doing? Hirut shook her head. She shakes her head now. She has come this far to return this box, to rid

herself of the horror that staggers back unbidden. She has come to give up the ghosts and drive them away. She

has no time for questions. She has no time to correct an old man’s pronunciation. One name always drags with

it another: nothing travels alone.

From outside, a fist of sunlight bears through the dusty window of the Addis Ababa train station. It bathes

her head in warmth and settles on her feet. A breeze unfurls into the room. Hirut looks up and sees a young

woman dressed in ferenj clothes push through the door, clutching a worn suitcase. The city rises

behind her. Hirut sees the long dirt road that leads back to the city center. She sees three women balancing

bundles of firewood. There, just beyond the roundabout is a procession of priests where once, in 1941, there

had been warriors and she, one of them. The flat metal box, the length of her forearm, grows cool on her lap,

lies as heavy as a dying body against her stomach. She shifts and traces the edges of the metal, rigid and

sharp, rusting with age.

“It has taken almost forty years of another life to begin to remember who she had once been.”

Somewhere tucked into the crevice of this city, Ettore is waiting two days to see her. He is sitting at his

desk in the dim glow of a small office, hunched over one of his photos. Or, he is sitting in a chair drenched

in the same light that tugs at her feet, staring toward his Italia. He is counting time, too, both of them

tipping toward the appointed day. Hirut stares at the sunlit vista pressing itself through the swinging doors.

As they start to close, she holds her breath. Addis Ababa shrinks to a sliver and slips out of the room.

Ettore slumps and falls back into darkness. When they finally shut, she is left alone again, clutching the box

in this echoing chamber.

She feels the first threads of a familiar fear. I am Hirut, she reminds herself, daughter of Getey and Fasil,

born on a blessed day of harvest, beloved wife and loving mother, a soldier. She releases a breath. It has

taken so long to get here. It has taken almost forty years of another life to begin to remember who she had

once been. The journey back began like this: with a letter, the first she has ever received:

Cara Hirut, They tell me that I have finally found you. They tell me you married and live in a place too small

for maps. This messenger says he knows your village. He says he will deliver this to you and bring me back your

message. Please come to Addis. Hurry. There is unrest here and I must leave. I have no place to go but Italy. Tell

me when to meet you at the station. Be careful, they have risen against the emperor. Please come. Bring the box. Ettore.

It is dated with the ferenj date: 23 April 1974.

The doors open again and this time, it is one of those soldiers she has seen scattered along the path to this city.

A young man who lets noise tumble in over his shoulder. He is carrying a new rifle slung on his back carelessly. His

uniform is unpatched and untorn. It is free of dirt and suited for his size. He is too eager-eyed to have ever held

a dying compatriot, too sharp with his movements to have ever known real fatigue.

“Land to the tiller! Revolutionary Ethiopia!” he shouts, and the air in the station flees the room. He lifts

his gun with a child’s clumsiness, aware of being observed. He points to the photograph of Emperor Haile

Selassie just above the entrance. “Down with the emperor!” he shouts, swinging his gun from the wall to the back

of the nervous station.

The waiting room is crowded, full of those who want to leave the roiling city. They breathe in and shrink away

from this uniformed boy straining toward manhood. Hirut looks at the picture of Emperor Haile Selassie: a

dignified, delicate-boned man stares into the camera, somber and regal in his military uniform and medals. The

soldier, too, glances up, left with nothing to do but hear his own voice echo back. He shifts awkwardly, then

turns and races out the door.

The dead pulse beneath the lid. For so long, they have been rising and crumbling in the face of her anger,

giving way to the shame that still stuns her into paralysis. She can hear them now telling her what she already knows:

The real emperor of this country is on his farm tilling the tiny plot of land next to hers. He has never worn a

crown and lives alone and has no enemies. He is a quiet man who once led a nation against a steel beast, and she

was his most trusted soldier: the proud guard of the Shadow King. Tell them, Hirut. There is no time but now.

She can hear the dead growing louder: We must be heard. We must be remembered. We must be known. We will not

rest until we have been mourned. She opens the box.

There are two bundles of pictures, each tied with the same delicate blue string. He has written her name in

loose-jointed handwriting on one, the letters ballooning across the paper folded over the stack and held in place by

string. Hirut unties it and two photos slide out, sticking together from age. One is of the French photographer who

roamed the northern highlands taking photos, a thin slip of a man with a large camera. On the back of the picture it

reads, Gondar, 1935. This is what we know of this man: He is a former draftsman from Albi, a failed painter with a

slippery voice and small blue eyes. He holds no importance except what memory allows. But he is in the box, and he

is one of the dead, and he insists on his right to be known. What we will say because we must: there is also a

photograph of Hirut taken by this Frenchman. A portrait shot while he visited the home of Aster and Kidane and

requested a picture of the servants to trade with other photographers or exchange for film. She turns away from it.

She does not want to see her picture. She wants to close the box to shut us up. But it is here and this younger

Hirut also refuses a quiet grave.

“She wants to close the box to shut us up. But it is here and this younger Hirut also refuses a quiet

grave.”

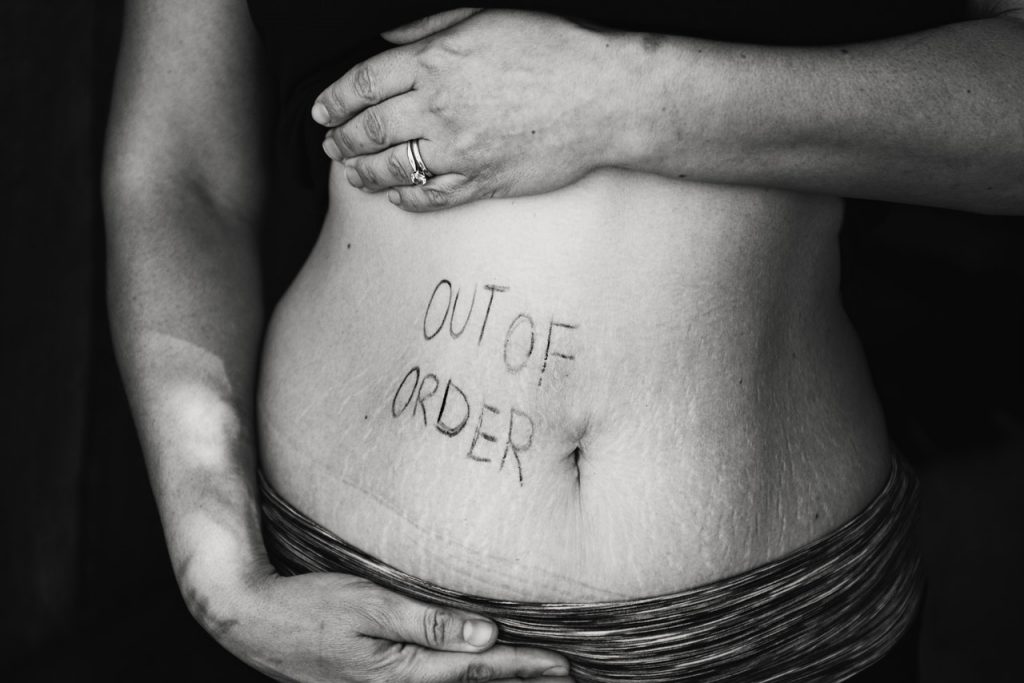

This is Hirut. This is her wide-open face and curious gaze. She has her mother’s high forehead and her father’s

curved mouth. Her bright eyes are wary but calm, catching light in golden prisms. She leans into the space in

front of her, a pretty girl with slender neck and sloping shoulders. Her expression is guarded, her posture

peculiarly stiff, absent the natural elegance that she will not know for many years is hers. She looks away from

the camera and struggles not to squint, her face turned to the biting sun. It is easy to see the sharp slope of

her collarbone, the scarless neck that rises from the V collar of her dress. It is this picture that will

preserve the unmarked expanse of skin that spreads across her shoulders and back. No other way to recall the

unblemished body she once carried with the carelessness of a child. And look, in the background, so far away she

is hard to see, there is Aster, pausing to watch, an elegant line cutting through light.

Excerpted from The Shadow King: A Novel. Copyright © 2019 by Maaza Mengiste. Used with permission of

the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

We hope you enjoy the book recommended here. Our goal is to suggest only things we love and think you might, as

well. We also like transparency, so, full disclosure: We may collect a share of sales or other compensation if you

purchase through the external links on this page.